Salvation is the Rock

O come, let us sing unto the LORD; let us make a joyful noise

to the rock of our salvation. - Psalm 95:1

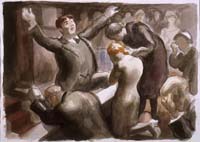

Grassroots religious revival meetings were popular subjects of American Regionalist painters during the 1930s. Salvation is the Rock is a masterpiece of the genre. This rare example of John Steuart Curry’s mature evangelical imagery, with its related watercolor and drawing, remained in Mrs. Kathleen Curry’s private collection until shortly before her death.

Raised in rural Kansas by strict Scots Covenanter parents, John Steuart Curry embraced the calling and commitment of his religion. Maturity deepened Curry’s faith, but the death of his brother and a friend during WWI led him to question his beliefs. The desperate years of the Great Depression intensified the artist’s doubt. By 1934, the year that he painted this work, Curry had become a celebrated member of the Regionalist triumvirate that included Thomas Hart Benton and Grant Wood.

Despite his misgivings, Curry’s religious background remained prominent in much of his work. Curry once stated that his style was formed “on the King James version of the Bible” and that he was “raised on hard work and the Shorter Catechism.” Using biblical imagery to impart his paintings with significance, Curry’s paintings use religion as a device to create parallels between biblical events and American culture.

Although two earlier paintings, Gospel Train and Prayer for Grace, 1929, are considered icons of Curry’s grassroots evangelical imagery, Salvation is the Rock, 1934, stands alone as a mature expression of the artist’s work. Preliminary studies reveal the artist’s creative process.

Originally Curry’s composition involved a preacher and his congregation. Throughout the studies, new levels of complexity become apparent. With the addition of a choirmaster and choir in the finished painting, Curry intensifies the emotional interpretation. These carefully controlled figures become foils to the charged, turbulent worshippers. By including figures that seem to fall off the edges, the view is pushed forward into the center of the action. The preacher with his open-armed “hallelujah pose” (found in Curry’s signature works, John Brown and The Fugitive) engages the viewer. Curry uses a vibrant brush stroke, monochromatic color and carefully placed accents of vivid red to bind the two areas of figures together.

Curry’s treatment of the subject matter, from the position of both participant and disconnected observer, reflects his own difficult relationship with religion. The complexities of control, blind trust and manipulation are palpably visual. The raw emotion of this painting and complexity of design give credence to the following comment by Thomas Hart Benton:

“It is not for me, yet standing, to judge our success as a whole. But I will risk this-whatever may be said of Grant Wood and me, it will surely able said of John Curry that he was the most simply human artist of his day. Maybe, in the end, that will make him the greatest.”

|

|